What History Forgot: India’s Greatest Dynasties and Their Rise and Fall

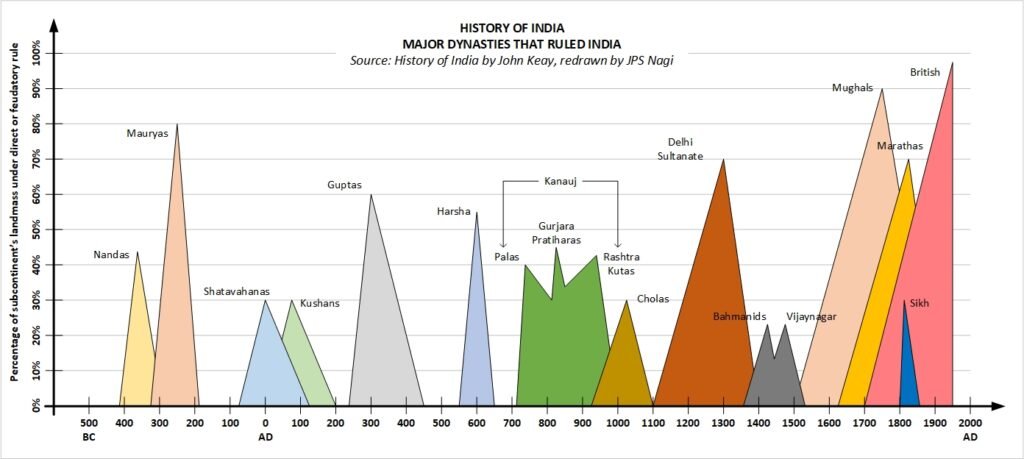

History often feels like a slow march forward, but in truth, it pulses—ebbing and flowing with the rhythm of empires rising and falling. Nowhere is this more evident than in the story of India’s rulers, whose reigns stretched across millennia, shaping not just land and law, but the very soul of the subcontinent. A graph, at first glance austere and analytical, tells this story in its own quiet way. Based on John Keay’s India: A History and redrawn by me, this visual reveals more than dates and names. It lays bare a breathtaking saga of power, ambition, unity, and fragmentation.

We begin around 400 BCE, when the Nanda dynasty first appeared on the scene. Their influence was notable, but short-lived. Their true legacy, however, may have been as the launching pad for something far greater—the Mauryan Empire. Under the leadership of Chandragupta and, later, the legendary Ashoka, the Mauryas managed to do what few before or after them would: unite nearly the entire Indian subcontinent. The towering peak of their control on the graph, nearing the full control of India, reflects not just territorial dominance, but a moment in time when a vast and diverse region pulsed to the beat of a singular empire.

Yet even Ashoka’s embrace of Buddhism and his pillar-edicts stretching from Afghanistan to Bengal couldn’t stop the tides of history. The Mauryas fell. And with them, unity gave way to a more fragmented landscape. Dynasties like the Shatavahanas and Kushans emerged—important, yes, but regional in scope. Their presence on the graph narrows, as if the land itself is exhaling, relinquishing centralized control in favor of scattered dominions.

Then came the Guptas, often seen as heralds of India’s classical age. Art, science, and philosophy flourished under their reign. While their territorial reach never rivaled the Mauryas, the Guptas lit a cultural fire whose warmth can still be felt today. But again, decline followed. After the Guptas, the center did not hold. Instead, it fractured—into Harsha’s brief northern consolidation, and then the tripartite struggles among the Palas, Gurjara-Pratiharas, and Rashtrakutas. Here looks like the jagged edge of a mountain range, each peak representing a dynasty rising to contest power, yet none strong enough to hold it all.

And so, we move forward, past the year 1000 AD, into a period of bold southern ambition. The Cholas originated from Tamil Nadu, and their seafaring prowess extended Indian influence as far as Southeast Asia. Their tenure is bold and bright on the graph, like a firework bursting from the south.

But the true shift is yet to come.

With the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate around the 13th century, India witnessed the emergence of the first major Islamic empire on its soil. The Sultanate expands, bringing architectural marvels, Persian influence, and a new style of governance. Its dominion rises sharply on the chart, commanding attention. The Bahmanids and Vijayanagar kingdoms follow, their stories entwined in a rich tapestry of trade, temple-building, and warfare in the Deccan.

Then, as if summoned by fate, the Mughals arrive.

The Mughal Empire is a return to scale—an echo of the Mauryas at their peak, and in many ways, its mirror. Babur’s conquest in 1526 sets the stage, but it’s Akbar who truly weaves the empire together, binding north and south, Muslim and Hindu, administration and art. The Mughal reign climbs to its height with a grace that speaks of poetry, palaces, and policy all moving in rhythm. Their near-total control of the subcontinent is a crescendo in this visual symphony, signaling the arrival of a new golden age.

Yet even empires bathed in marble and poetry are not eternal.

By the late 17th century, cracks appear. The Marathas rise from the western heartlands, agile and defiant. Their growth on the graph is steep and muscular, a counterforce to Mughal decline. And in the far north, another fire is lit—brief, but brilliant. The Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh holds the northwest with an iron resolve and a reformist vision. Though narrow in span, they were bold, like a mountain standing alone.

And then comes the last and longest shadow—British rule. Its ascent is slow, methodical, and irreversible. By the mid-19th century, the British have what no other had: complete dominance. The graph rises to 100%, a stark and sobering testament to colonial power. But unlike other empires, this one did not arise from Indian soil. It came from across the seas, and with it came railroads and bureaucracy—but also exploitation, famine, and the loss of sovereignty.

The story ends not with empire, but with a question. After the British peak comes independence, but that lies beyond the scope of this graph. It is a story yet unfolding, a continuation that defies visualization, for it belongs not to a dynasty, but to a democracy.

In the end, what does this graph truly show us? That power is transient. That no matter how vast the land controlled or how high the peak, every dynasty falls. But also, that India endures. Through every change of hand, language, faith, and flag, the land persists—remembering, adapting, waiting.

A graph can never tell the full story. But this one whispers enough to make us pause, reflect, and perhaps even marvel at the resilience of a civilization that has seen it all—and still rises.

Bibliography

- India: A History by John Keay (Paperback)

- India. A History by John Keay (2 Volume Set)

- India. A History by John Keay (Folio Society Edition)

👁️ 342 views