The Pen of Middle-earth, Part III: The Script of Arda – How Tools Shaped Language

Every great invention begins as a gesture. For Tolkien, that gesture was a stroke of ink. Before a single word of The Lord of the Rings was written, before hobbits had names or Númenor had fallen, his pen was already shaping the sound and rhythm of his imagined languages. His worlds were born not in prose, but in script and the script itself was born from the mechanics of the pen.

When Steel Meets Syntax

Tolkien didn’t just invent alphabets; he engineered them. Tengwar, Cirth, Sarati – each system obeyed phonetic logic and aesthetic symmetry. Yet beneath that order lies something humbler: the influence of a broad, slightly oblique nib.

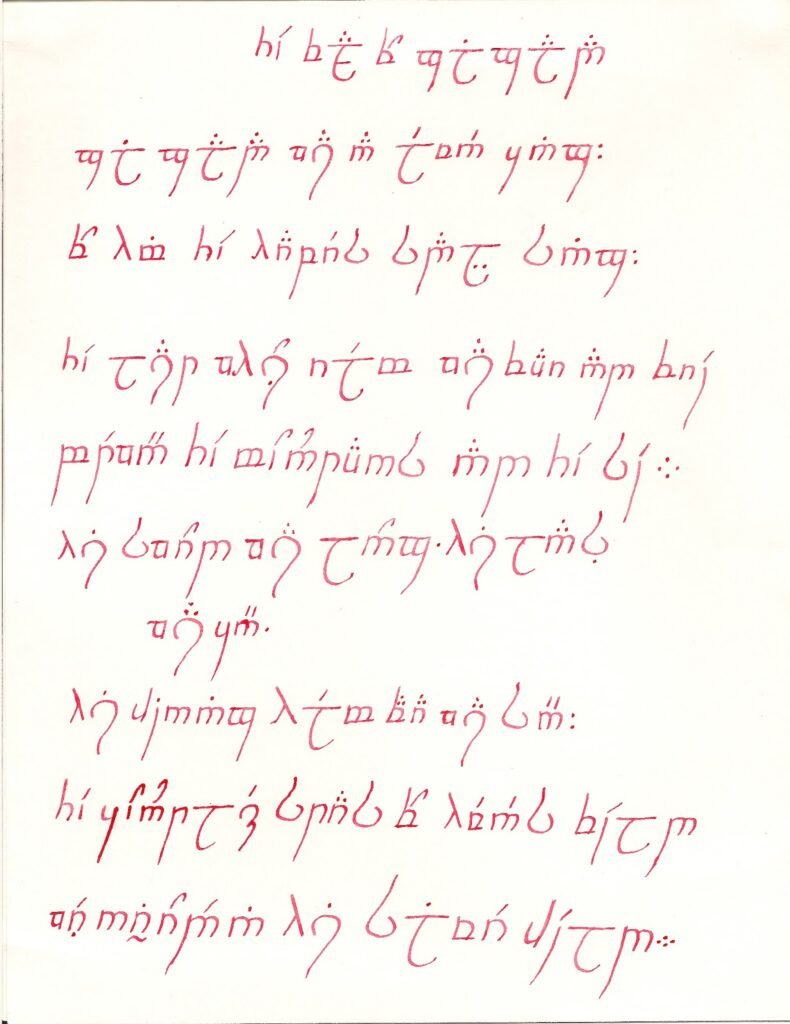

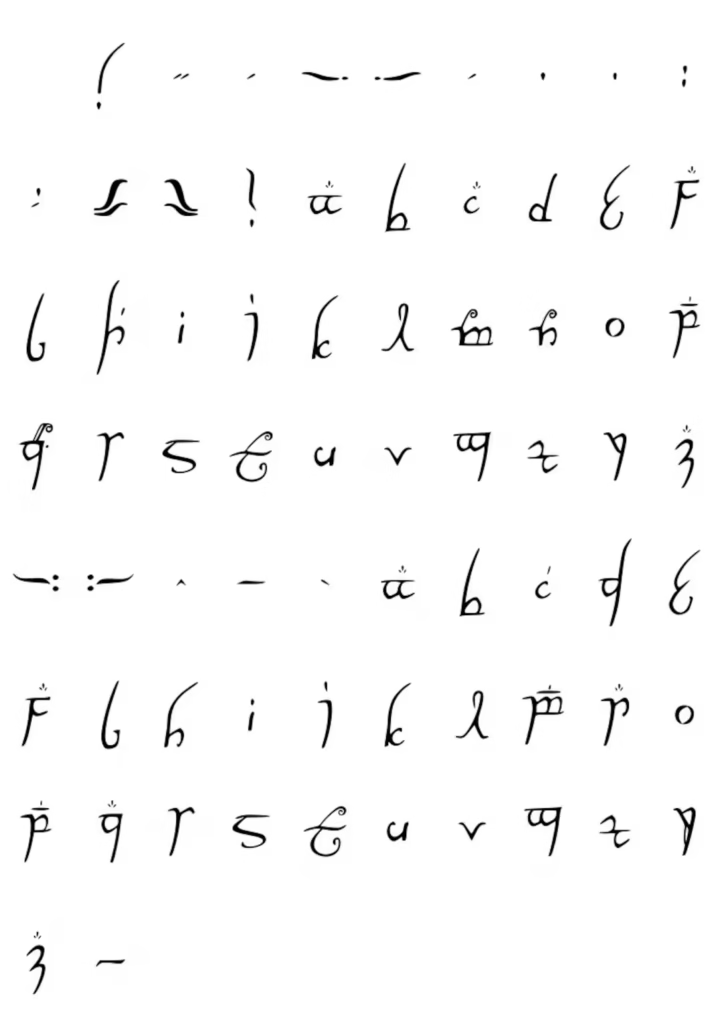

The shapes of Tengwar are unmistakable – elegant verticals, sweeping hooks, and fine connective lines. They are perfectly suited to a pen held at a 45-degree angle. Every thick downstroke and tapering upstroke mirrors the natural rhythm of a dip pen. These weren’t arbitrary symbols; they were designed for the tool in Tolkien’s hand.

This is the subtle genius of Tolkien’s craft: the physical properties of his writing instrument became part of his world-building grammar. You could say the Esterbrook 314 Relief was as much a design collaborator as the man himself.

Script as Sound

To understand how deeply the pen influenced his languages, you have to see what Tengwar was meant to do. Each stroke isn’t just decorative; it represents phonetic flow. The tall, straight characters carry the weight of consonants; the delicate curls whisper vowels. The result is a visual rhythm that mirrors the spoken melody of Quenya and Sindarin – both languages Tolkien wrote to be beautiful to the ear and balanced on the tongue.

When you watch a modern calligrapher trace Tengwar with an oblique nib, you realize how seamlessly the visual and the auditory fit together. The line isn’t trying to look elegant; it is elegant because it follows the same rhythm as the speech it represents.

The Echo of Medieval Hands

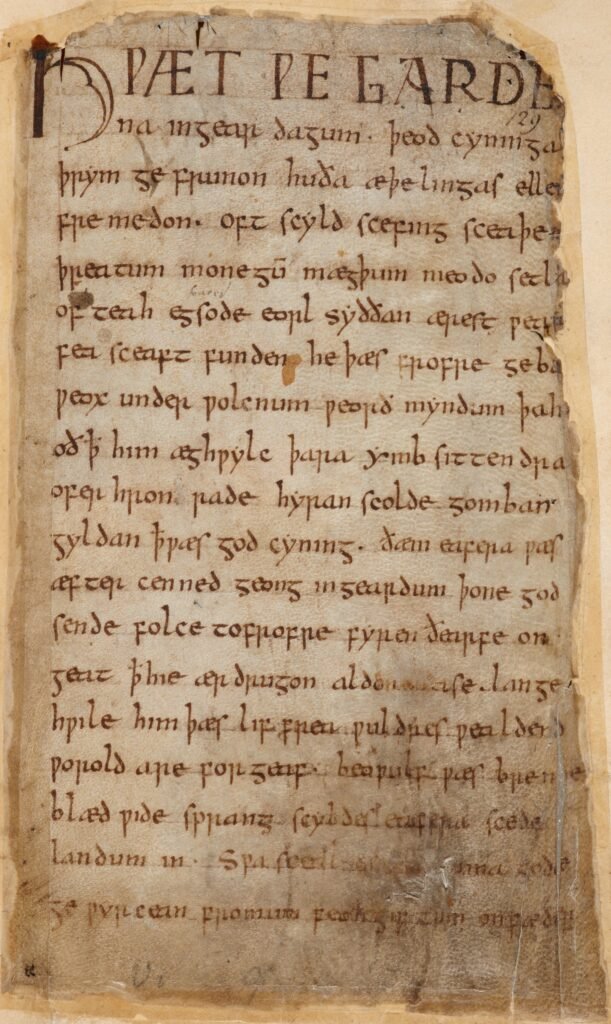

Tolkien knew medieval manuscripts intimately. He had spent decades studying the scripts of Anglo-Saxon and Middle-English texts. Those scribes wrote with quills that forced them to think about angle and width just as he did. Their scripts – Carolingian, Insular, Gothic – were full of thick-and-thin contrasts that made every word a design.

When he designed Tengwar, he wasn’t just making a new alphabet; he was resurrecting a tradition. The Elves’ calligraphy carries the DNA of monastic scriptoriums – patient, formal, but alive. The difference is that where medieval monks copied scripture, Tolkien wrote creation myths.

The Logic of Form

There’s a precision in his letterforms that mirrors linguistic structure. In Tengwar, a single modification – a dot above or curl below – can change meaning, tense, or phonetic value. The same modular thinking defines his approach to language: roots, stems, suffixes, inflections. You can sense the academic mind behind the artistry.

Yet there’s also warmth. His broad-nibbed lines curve gently, never rigid. Even his invented alphabets feel written by a living hand, not printed by machine.

Ink as a Living Medium

Look at his maps or title pages: ink density changes mid-word, the nib re-dipped halfway through a stroke. These imperfections give the illusion of age – as if the text were copied from a thousand-year-old codex rather than written in 1954.

That’s why reproductions of his manuscripts never look quite the same. The physical ink interacts with the paper, pooling slightly where he paused, thinning where he lifted. Each mark is a trace of hesitation, of thought. Middle-earth was written with pauses.

The Hand as a Tool of Myth

Tolkien’s languages didn’t exist in isolation. Their scripts dictated how his peoples saw art, architecture, and ornamentation. The elegant symmetry of Tengwar mirrors the arches and runes of Elven halls; the harsh geometry of Cirth echoes Dwarvish craft. All of it came from the same habit: a man thinking with his hand.

He once wrote, “The invention of languages is the foundation. The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.” It’s easy to imagine him adding, silently, and the letters are the bones of that world.

A Scholar’s Magic

There’s a tension in Tolkien’s craft that every creator should envy. He was a scholar who refused to let precision smother wonder. He knew that language, like art, breathes only when made by hand. That’s why Tengwar feels alive – it isn’t just readable; it’s performative. Writing it is an act of devotion.

You can see the same humility in the way he handled his tools. A cheap dip pen, a bottle of iron-gall ink, and an imagination vast enough to hold the history of Arda. He didn’t need perfection – just permanence.

Reflection

The Script of Arda is more than a collection of symbols. It’s a record of human touch – of how a steel nib could carve myth into paper. Tolkien’s alphabets remind us that creation doesn’t always begin with inspiration; sometimes it begins with resistance – the drag of ink, the imperfection of line, the hesitation before the next stroke.

That friction, that slowness, is where worlds are born.

Essays in this series:

- The Pen of Middle-Earth: Tools that shaped J.R.R. Tolkien’s worlds

- The Pen of Middle-earth, Part I: Ink and Imagination – The Hand That Built Middle-earth

- The Pen of Middle-earth, Part II: The Instruments of Creation – Tolkien’s Pens, Nibs, and Inkwells

- The Pen of Middle-earth, Part III: The Script of Arda – How Tools Shaped Language

- The Pen of Middle-earth, Part IV: Recreating Tolkien – Modern Calligraphers and Fountain Pen Enthusiasts

- The Pen of Middle-earth, Part V: The Slowness of Creation – What Tolkien’s Pen Teaches Us

👁️ 34 views