Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 6: Saints, Seekers & the Soul of Punjab

There’s a moment in every story when the music pauses – when love turns into longing, and longing turns into prayer.

In Punjab’s folklore, that moment never truly ends.

After the tragic beauty of Heer Ranjha or Sohni Mahiwal, what follows isn’t despair – it’s awakening. The lovers’ cries dissolve into the verses of saints, poets, and seekers who taught the people how to turn sorrow into song, and devotion into daily life.

This is the philosophy that gave Punjab its soul – a quiet, inclusive spirituality woven into its folklore through the teachings of Baba Bulleh Shah, Guru Nanak, Mian Muhammad Bakhsh, Shah Hussain, Waris Shah, and countless others whose words blurred the lines between religion and humanity.

The Saints Who Sang to the People

Unlike the distant gods of mythology, the saints of Punjab were people who walked among farmers, artisans, and wanderers.

They spoke the language of the soil – not Sanskrit, Arabic, or Persian, but Punjabi, the people’s tongue.

Their words were not sermons; they were songs. And because of that, they became folklore.

They sang in the fields, at wells, in gatherings under banyan trees. Their verses flowed like the rivers – simple enough for a child to understand, deep enough for a philosopher to ponder.

Guru Nanak sang:

“Pawan guru, pani pita, mata dharat mahat.”

(Air is the teacher, water the father, earth the great mother.)

And Bulleh Shah answered, centuries later:

“Masjid dha de, mandir dha de, dha de jo kuch dainda —

Par kise da dil na dholin, Rabb dilan vich rehnda.”

(Demolish mosque, demolish temple, destroy what divides —

But never break a human heart, for that is where God resides.)

Their poetry wasn’t just spiritual – it was radical. It made holiness human.

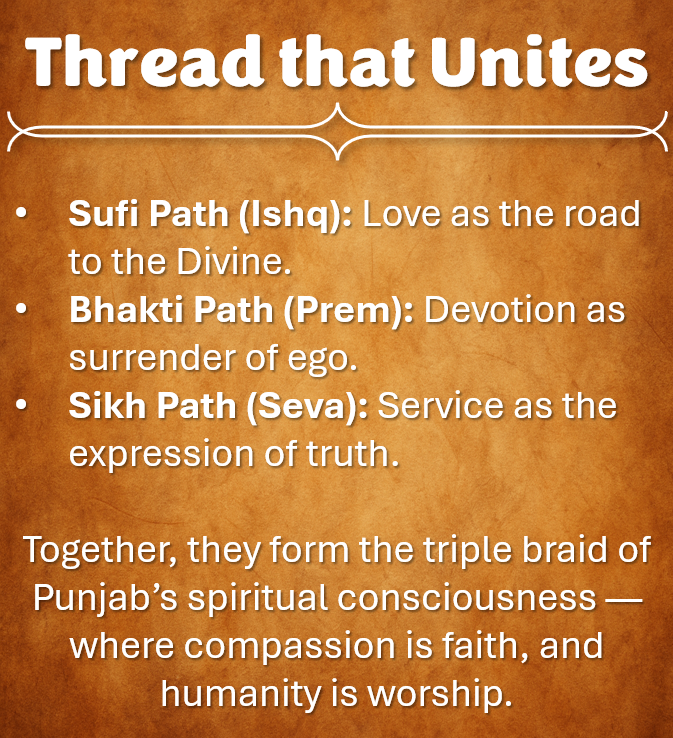

The Meeting of Sufi and Bhakti

Punjab was a crossroads of faiths, where Sufi mysticism met the Hindu Bhakti movement and later found harmony within Sikh philosophy.

The result was not a clash, but a conversation – centuries long, carried in verses, music, and folklore.

Sufis like Shah Hussain, Sultan Bahu, Bulleh Shah, and Waris Shah spoke of divine love through human metaphors.

Bhakti poets like Namdev, Kabir, Ravidas, and later the Sikh Gurus, spoke of devotion that transcended caste and creed.

They all sought the same truth: that the Divine is not separate, but immanent – found in breath, work, compassion, and love.

Their ideas seeped into the collective mind of Punjab, transforming its folklore into something profoundly secular – a spiritual democracy of the heart.

Bulleh Shah: The Poet of Rebellion

No one embodied this fusion more than Baba Bulleh Shah (1680–1757).

He was the bridge between Sufi mysticism and folk wisdom, between the mystic’s solitude and the peasant’s struggle.

Bulleh’s verses appear simple, but they cut through hypocrisy like fire through silk. He mocked empty ritual, questioned power, and placed the human soul above dogma.

“Bulleya ki jaana main kaun?

Na main momin, na main kafir, na main moosa na pharaoh.”

(Bulleh, who am I?

I am neither believer nor infidel, neither Moses nor Pharaoh.)

His defiance made him beloved – and dangerous. Religious authorities shunned him, but the people embraced him. His kafis became songs of liberation, sung by farmers, fakirs, and lovers alike.

Even today, his words echo in qawwalis and rock ballads across Pakistan and India – proof that truth, once sung, never dies.

Mian Muhammad Bakhsh: The Philosopher of Compassion

In Saif-ul-Malook, Mian Muhammad Bakhsh (1830–1907) turned folklore into philosophy.

He retold an old Persian legend but gave it a Punjabi soul – turning the prince’s adventure into a metaphor for the soul’s journey toward enlightenment.

“Duniya ek paheli hai, samajh na aave koi.”

(The world is a riddle no mind can solve.)

His verses reflect humility and grace – reminders that spiritual understanding comes not from escape, but from empathy.

Through him, folklore learned to meditate.

Guru Nanak and the Everyday Sacred

Guru Nanak’s teachings are perhaps the foundation on which Punjab’s moral consciousness stands.

He rejected the hierarchies of religion, affirming instead that truth lies in honest work, sharing, and remembrance of the Divine through service (seva).

His hymns, preserved in the Guru Granth Sahib, are not distant philosophy – they’re living folklore, sung as shabads in gurdwaras and homes across the world.

And because he sang in the language of the people, his words crossed boundaries of faith.

For centuries, both Hindus and Muslims called him Baba Nanak. He belonged to everyone.

A Folk Religion of Love

All these saints – Sufi, Bhakti, Sikh – built something extraordinary together: a folk religion of love.

It wasn’t organized or institutional; it was lived.

In every Punjabi village, you’ll find a small shrine where a Muslim saint’s grave and a Hindu deity’s image sit side by side, visited by Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims alike.

This coexistence, fragile yet enduring, is one of Punjab’s greatest gifts to the world.

It taught generations that divinity doesn’t ask for uniformity – it asks for unity.

Folklore as a Mirror of Social Conscience

The influence of these saints went beyond faith – it shaped Punjab’s social ethics.

They spoke against caste, against gender discrimination, against greed and corruption.

Their language was the language of farmers, potters, and shepherds – accessible, honest, forgiving.

That is why even in modern Punjabi sayings, their spirit lingers:

“Rabb dilan vich rehnda hai” (God lives in hearts),

“Kam karo, vand chhako” (Work hard, share what you earn).

These aren’t just moral lines – they’re folklore’s DNA.

The Eternal Dialogue

The beauty of Punjabi spirituality is its refusal to end the conversation.

Every generation reinterprets these teachings anew – from Sufi qawwals in Lahore to gurbani singers in Amritsar, from poets like Shiv Batalvi to the diaspora musicians who turn Bulleh Shah into jazz.

The question remains the same: How do we live truthfully in a divided world?

And every age answers it in its own rhythm.

Closing Reflection

Punjab’s folklore found its moral compass not in kings or conquerors, but in saints who walked barefoot among the poor.

They turned love into philosophy, protest into poetry, and devotion into daily practice.

Their words still breathe in the air of this land – every time a child is taught kindness, every time a song praises unity, every time a stranger is fed.

Perhaps that’s the truest miracle of all:

That the same soil that grew wheat and war also grew wisdom – and that wisdom still sings.

Links to the essays in the series:

- Echoes of the Five Rivers: A Journey Through Punjabi Folklore

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 1: The Soul of Punjab and Its Stories

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 2: Themes, Motifs & the Soul of Punjabi Storytelling

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 3: Folk Beliefs, Rituals & the Living Spirit of Punjab

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 4: Folk Music, Songs & the Voice of the Land

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 5: The Qissas – Love, Rebellion, and the Eternal River

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 6: Saints, Seekers & the Soul of Punjab

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 7: Legends of Valor, Justice & the Everyday Hero

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 8: Folklore & Modernity – The Stories That Refuse to Die

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 9: Reflections, Continuity & the River That Remembers

👁️ 109 views

Share this post :

Archives

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

Categories

Missives from Planet Nagi

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get insightful stories, updates, and inspiration delivered straight to your inbox. Be the first to know what’s new and never miss a post!

1 Comment on “Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 6: Saints, Seekers & the Soul of Punjab”

Salute