Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 8: Folklore & Modernity – The Stories That Refuse to Die

Every story, if it’s loved enough, learns to survive time.

It changes shape, slips into new languages, finds new singers.

It becomes a song, a film, a memory, a meme.

That’s what happened to Punjabi folklore – it didn’t vanish into history; it reinvented itself.

From the open courtyards of villages to the glowing screens of YouTube, the qissa, the boli, and the vaar have found new homes.

The storyteller’s lantern is now a spotlight, and the same old tales of Heer, Sohni, and Dulla Bhatti play out in pixels and poetry alike.

From Oral Tales to Silver Screens

The transition from oral storytelling to cinema was not a rupture – it was a continuation.

Punjabi filmmakers of the mid-20th century didn’t invent new plots; they simply gave faces to familiar voices.

The 1932 film Heer Ranjha (India’s first talkie based on a Punjabi qissa) opened the floodgates. Over the decades, dozens of adaptations followed – each retelling the same story, but reflecting the era’s mood.

In the 1970s, Heer Ranjha was pure tragedy; by the 1990s, Heer Ranjha became a metaphor for love defying social boundaries.

Today, digital creators reinterpret it through short films and music videos, connecting centuries through rhythm and romance.

In every version, the core remains the same – love as resistance, truth as devotion.

The Folk Enters the Studio

Folk music, once confined to fields and fairs, has become global identity.

Artists like Surinder Kaur, Lal Chand Yamla Jatt, and Gurdas Maan transformed traditional songs into modern anthems. Their melodies traveled beyond Punjab – to London, Toronto, Vancouver – carried by those who left home but never left its sound.

Even now, Coke Studio Pakistan revives Sufi qissas like Sohni Dharti and Heer Waris Shah, blending electric guitars with tumbis.

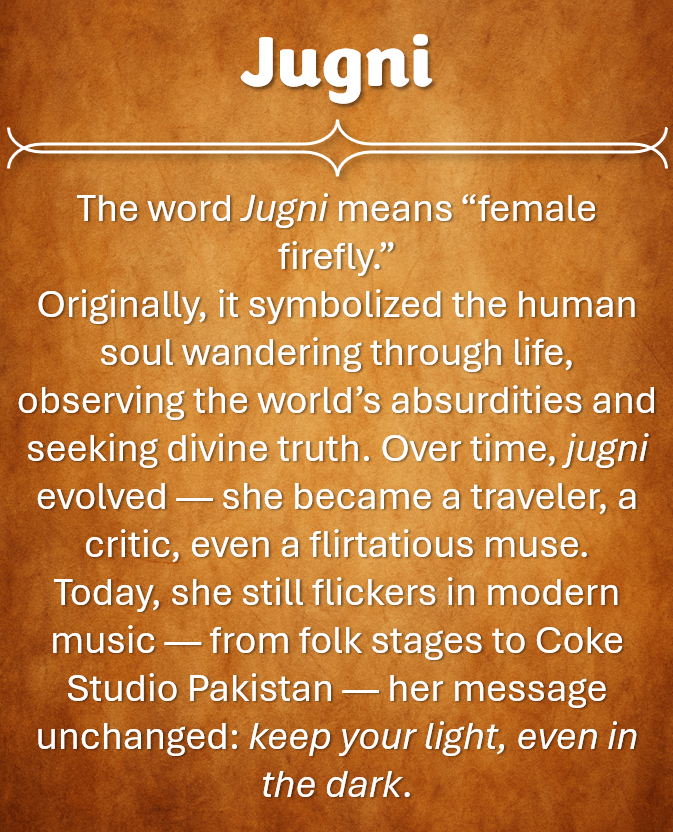

The song Jugni, once a wandering soul, now dances in pop beats and EDM remixes, yet her message is still the same:

be curious, stay alive, seek light in darkness.

Technology didn’t erase folk tradition; it amplified it.

Every reel of a giddha dancer, every remix of a boli, is another ripple of the same old river.

Diaspora and the Story in Exile

Something beautiful happened when Punjabis migrated – the stories migrated with them.

In London, Heer Ranjha became a stage play performed by second-generation youth.

In Canada, Bhangra became both a dance and an identity.

In California, truckers still decorate their rigs with verses of Sohni Mahiwal or portraits of Dulla Bhatti, painted with chrome and nostalgia.

For many in the diaspora, folklore became a lifeline – a way to stay rooted when the soil beneath them changed.

The qissa was no longer just a story of two lovers; it became the story of migration itself – separation, longing, and the hope of return.

When a young Punjabi in Melbourne listens to Heer Waris Shah on Spotify, they are hearing not just a love story – they are hearing their grandmother’s accent, their ancestors’ rivers, their own reflection.

Women’s Voices Return

Something else has shifted too – the way women reclaim these stories.

Modern reinterpretations of Heer, Sohni, and Sahiban are no longer about tragedy alone; they’re about choice, strength, and rebellion.

In theatre productions, academic essays, and indie films, these women are being rewritten not as victims, but as visionaries.

Writers like Amrita Pritam and Bapsi Sidhwa re-imagined Heer and Sohni as voices of conscience – women who spoke truth to power through love.

Their modern avatars are artists, poets, travelers – not just waiting for fate, but shaping it.

It’s as if the daughters of Punjab are now rewriting their mothers’ myths – and the folklore is finally listening.

Folklore in a Digital Age

Open YouTube, and you’ll find dozens of channels dedicated to Punjabi folk tales – narrated in English, Hindi, or pure Multani.

Folk archives at universities in Patiala and Lahore are digitizing old manuscripts, while AI voices read Heer Waris Shah in perfect rhythm.

Even memes carry echoes of tradition – a funny jugni caption on Instagram, a viral TikTok boli dance, or a remix that turns Heer Ranjha into hip-hop.

Some might call it dilution. I call it evolution.

Every age re-invents its folklore in its own voice.

The medium changes, the message deepens.

And perhaps this is the greatest victory of Punjabi folklore – that it refuses to become a relic.

Between Faith and Pop Culture

The beauty of modern Punjabi storytelling lies in its duality.

It can sing in the language of devotion and the beat of a nightclub in the same breath.

You can hear Heer Ranjha at a village fair and again, transformed, in a rap lyric about heartbreak and exile.

This coexistence – the sacred and the street – is what keeps the culture alive.

Folklore here isn’t preserved under glass; it’s out dancing in the rain, unafraid to get dirty, unafraid to change.

The Critics’ View: Preservation or Performance?

Of course, not everyone celebrates this evolution.

Cultural critics often worry that in chasing entertainment, we’ve lost authenticity – that bhangra beats have replaced soulful ballads, and digital glamour has silenced oral depth.

There’s some truth in that. When folklore becomes commodity, something tender is lost – the intimacy of shared space, the breath between words, the silence after a song.

But perhaps the real challenge isn’t to freeze tradition – it’s to reconnect with its spirit.

Every time someone learns a folk song, records their grandmother’s story, or paints Sohni on a canvas, they are not commercializing folklore – they are keeping it alive.

The question isn’t whether folklore will change. The question is whether we will still listen.

Across Generations

In recent years, schools in Punjab and abroad have begun teaching folklore as part of cultural heritage programs.

Children perform Heer Ranjha in classroom plays; diaspora youth learn boliyan through YouTube tutorials.

Old stories are finding young tongues again.

When my daughter once asked me why all Punjabi tales end sadly, I told her, “They don’t end sadly. They end truthfully.”

She smiled and said, “Then maybe I’ll write one with a happy ending.”

And I realized – that’s how folklore survives.

Not by repeating, but by renewing.

Closing Reflection

Folklore was never meant to stay still.

It was born to move – from mouth to mouth, heart to heart, and now, from screen to screen.

Maybe that’s why, no matter where you go in the world, if you hear a dhol, your feet still know what to do.

Because behind every beat, every verse, every voice, is a memory that refuses to die – the voice of a land that taught the world how to love, how to laugh, and how to keep singing even when everything else changes.

And perhaps that’s the greatest story Punjab ever told – not the tale of lovers or kings, but of a people who turned their pain into poetry and their poetry into immortality.

Links to the essays in the series:

- Echoes of the Five Rivers: A Journey Through Punjabi Folklore

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 1: The Soul of Punjab and Its Stories

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 2: Themes, Motifs & the Soul of Punjabi Storytelling

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 3: Folk Beliefs, Rituals & the Living Spirit of Punjab

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 4: Folk Music, Songs & the Voice of the Land

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 5: The Qissas – Love, Rebellion, and the Eternal River

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 6: Saints, Seekers & the Soul of Punjab

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 7: Legends of Valor, Justice & the Everyday Hero

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 8: Folklore & Modernity – The Stories That Refuse to Die

- Echoes of the Five Rivers, Part 9: Reflections, Continuity & the River That Remembers

👁️ 108 views